Dad, Eric, continued to follow the occupation of his father, Melvyn, and both Grandfathers, William Badcock and Isaac Richardson, that of a mixed farmer growing various crops and the running of stock.

The family held to the philosophy of “not having all eggs in the one basket”, the thought being that if one segment was down or should fail the other activities would carry them through.

Grandfather, Melvyn, also held to the stance of never buying dear seed and which stood him in good stead time and again in his life as a farmer. The thought behind this was to buy in when the price was low, and not only would this mean a smaller initial outlay but a more likely profit, even if this was only modest, but this was safer than buying in when the price was high with the possibility of a loss should prices fall.

Another saying which I used to regularly hear, particularly by Uncle Trevor, was “it is not what you can make on a farm but what you can save on a farm”. An important ingredient to this saying was to be as self sufficient in food as possible, consequently most families maintained a large garden and orchard, run poultry for eggs and meat, made their own butter and regularly killed sheep for meat. Candles and soap for a period was also made by earlier generations and many garments made by sewing and knitting. Also closely connected to this saying were several others, “a stitch in time saves nine” and “you must cut the coat to suit the cloth”.

Livestock

Sheep

Until the build up of the dairy herd by Dad and Mum in the 1960s sheep were the most common animal being run. At Grandfather Badcocks only a small breeding flock was run of from 100 to 150 ewes but this was added too by the yearly purchase of store stock for fattening and then resale. In some years up to four hundred sheep would be purchased, fattened and sold. The profit from this activity in the 1920s was as much as fifteen shillings per head but by the 1930s was as low as five shillings a head.

These sheep were frequently purchased at the Cressy and Bracknell sales and on other occasions from nearby farmers. The Dorset and Border Leicester breeds were the most commonly sought after, as they were hardy and produced excellent meat.

When wool became very valuable at the time of the Korean War in the early 1950s, it reaching a pound a pound, many farmers increased their flocks and moved to more wool breed sheep, such as Corriedales and Polworths but still mating them to meat type breeds.

Uncle Trevor was at the forefront of the change with his income one year being sufficient to buy a brand new Mercedes car.

For a number of years Grandfather Badcock ran a Lincoln sheep stud these being kept in the small paddocks around his “Stoke” home. Dad would sometimes recall that one ewe over a year reared a set of triplets and also cut 26lbs. of wool. On one occasion his father sent one of these stud rams to the Sydney Show.

Until the mid 1950s most live stock were moved from place to place on foot with flocks of sheep and herds of cattle moving along roads being a common sight. At times while I was at school at Bishopsbourne, flocks, sometimes consisting of thousands of sheep would pass through the town, in the spring heading to summer feeding grounds in the Western Tiers mountains to the south, then in the autumn moved back home. Herds of cattle would also be seen passing the school.

Uncle Trevor recalls some large herds of cattle moving along the Green Rises road as they were being trekked from Oatlands, where they had been purchased, to the Northwest Coast of Tasmania, a distance of some 140 plus miles. The drover was frequently a Mr. Burfett with him travelling by horse and cart and accompanied by a half dozen dogs, they riding in open hessian bag kennels beneath the cart. When a dog became knocked up he would be recalled and another sent out to help guide and control the herd along the road. These dogs, Uncle Trevor recalls, were very skilled.

When sheep were sold from “Stoke” and later from “Stratheden” and “The Grange” farms up till the early 1950s, they would be walked along the road to the Little Hampton railway station, about three miles distant, and loaded onto rail stock trucks. These trucks were double decked with each deck holding about 30 sheep.

Pigs

These were regularly run by Grandfather Badcock although rarely by his sons they becoming tired of them due to the havoc that the pigs caused around the farm. Often the pigs would be grazed on the pea stubble for fattening but with the fences not being sufficiently strong would regularly escape to other parts of the farm causing damage.

The pigs would be slaughtered on the property with three kills mostly being made over the winter months. The pigs would be cut up and converted into hams, all undertaken at the farm.

A considerable amount of time and effort was required for the production of well cured hams.

The pigs would mostly be grown to around 200 pounds in weight although Dad would sometimes mention that one pig weighed as much as 333lbs. Once cured the hams would be suspended from hooks attached from the ceiling and on occasions so many hams would be hanging the family wondered if the ceiling might fall in. These hams were supplied to the Brisbane Hotel in Launceston, Saunders and Bailey at Bracknell as well as to other outlets.

Cattle

Until the late 1950s cattle were mostly run as a sideline activity with most farmers milking up to a half dozen cows to keep the house in milk and butter with the surplus butter being sent to the Mart in Launceston or shop outlet. The skimmed milk would not be wasted with it being fed to the calves or pigs.

Grandfather Badcock milked three or four cows until his mid seventies only stopping when his arthritis became too severe. In his later years the milk would be separated and the cream sent by can several times a week by carrier to the butter factory. To get the filled cans to the road gate for pickup, Grandfather would load the cans onto a push cart that had been made from an old baby’s pram and shuffle the hundred yards each way.

At “The Grange” by the late 1950s sheep and crop revenues were in decline but with dairying providing good returns, the cow numbers began to be built up and eventually the decision made to build a dairy and install a milking machine.

This was undertaken for the milking season of 1960 and I still clearly remember spending the entire September school holidays mixing and carting cement. With the walls and floor made entirely of concrete, also a fairly large spread in the holding yards, it involved a considerable amount of heavy work. I remember being quite pleased when holidays finished and I could escape back to school.

By the time the milking machine became operational some 14 cows were being milked by hand and on one evening I remember milking each one and which took me about three hours to complete. The original dairy setup enabled three cows at a time to be milked with the next three waiting their turn in an adjoining bay.

Although on today’s dairy set up it would be considered very basic and slow, at the time it was a major advance on hand milking and made it possible to run a far greater number of cows. Dad was almost 50 years of age when the dairy was commenced and gradually built the herd up to near 90 milking cows before starting to reduce. Once the numbers got down to around 40 cows the dairy company informed that it was no longer economic to collect the bulk milk and the dairy was closed down. By this time Dad was in his mid seventies and although the dairy had been a tie, it had provided a reliable and reasonable income for the family over the previous 25 years.

Before the machine was put in, milking would take place in the open yard near the house. Seating would be provided by a one legged T shaped stool with the milk bucket placed between the legs.

To avoid being kicked the head or shoulder would be buried into the flank of the cow, even so one was always on the alert for the cow to kick or move forward spilling the milk. Sun burnt or cracked teats were sometimes a problem when milking.

Also milking in the open when raining was not much fun as the water would run off the cow saturating ones arms and legs. Another hate was having to milk the cows after having been out for the day and particularly having to change and leave the comfort of the fire on a cold wet day with plenty of mud around.

Poultry

Almost all families had a few chooks around and they mostly roamed free range on the farm. Their eggs produced was very welcome, even essential, for cooking in the home with sale of the surplus helping to bring in some pocket money for the household.

The surplus eggs were usually cleaned and packed up on a Thursday afternoon or evening, ready to catch the carrier to Launceston on the next day. With some nests not being located clutches of chickens, often as many as a dozen little chicks at a time, would make their way home thus keeping up the fowl numbers. These would be reared with a good number being killed and dressed when big enough and sent to the Mart in Launceston for sale, the income again helping with household needs.

Grandfather Badcock also kept geese and would regularly kill and dress these for their personal use and with each family receiving one either at Christmas or at Easter time. Sometimes us grandchildren would go to the pond where the geese mostly lived and remember on more than one occasion beating a hasty retreat ahead of a charging, hissing, squawking goose.

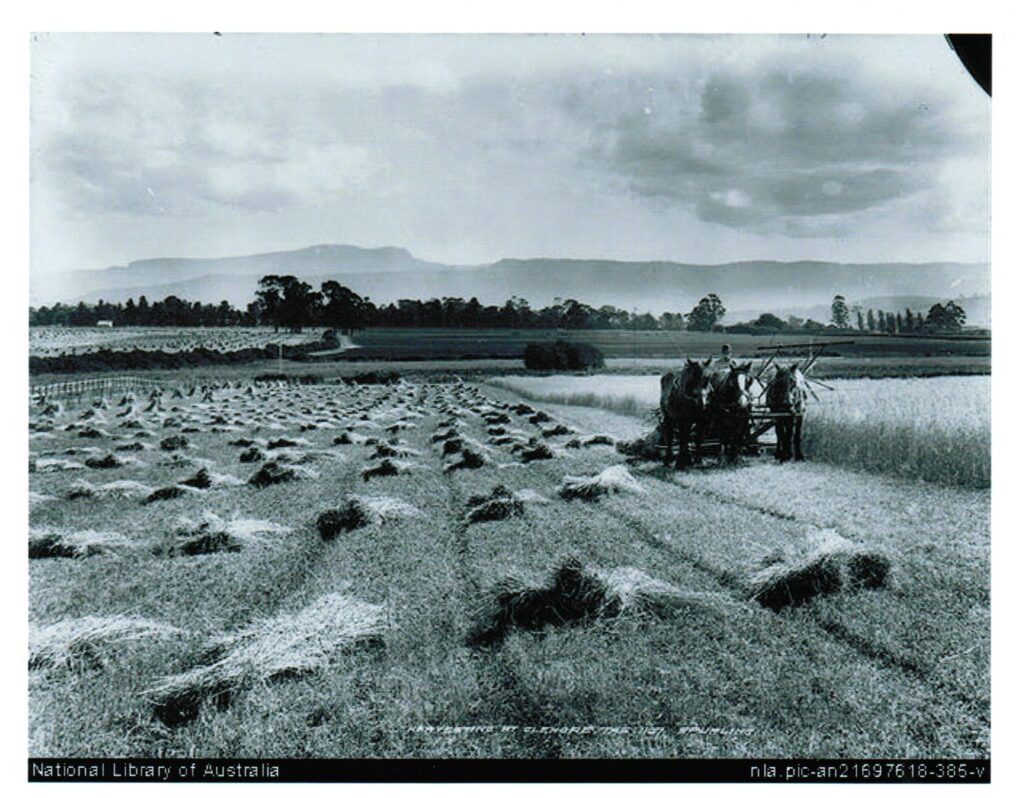

Cropping

Until the 1950s cropping was the major farming activity for Dad and his brothers, as well as his father Melvyn and several previous generations on the Badcock family line.

An indication of emigrant John Badcock’s farming activities is had when he was declared insolvent on 22 June 1861 and it is apparent that cropping formed a major part of his activity.

Items listed in The Examiner newspaper were as follows –

1 stack of wheat, 150 bushels

50 bushels wheat in straw

60 bags oat screenings

25 bags wheat screenings

270 bushels rye grass seed

200 bushels rye grass in chaff

2 stacks of hay, about 40 tons

3 stacks of hay, about 60 tons

3 stacks, wheat straw

2 stacks, oaten straw

3 bags, linseed in chaff

10 bags of potatoes

The entire horse Lincoln

1 bay gig horse

1 chestnut plough horse, 4 years

1 bay plough horse, 2 years

3 breeding sows

1 clod crusher

ploughs, grindstone, water cart and casks, cart frames etc.

180 pieces sawn timber. Terms Cash.

In William Badcock’s diaries there are constant references to ploughing, cultivating, drilling and harvesting various crops. These crops centred around wheat, oats, peas, barley, grass seed and the fodder crops of rape and turnips. A few acres of potatoes were often grown as a side line crop.

Flax at times was grown by William, Melvyn and Dad and with water becoming available from the Cressy-Longford Irrigation Scheme other crops were planted by various family members and included opium poppies, canning peas and beans, potatoes, corn, onions and canola.

Grandfather, Melvyn, on moving to “Sunny Rises” farm in 1910 was 31 years of age and by this time had been full time farming for 17 years and by then was well versed in cropping and in the main continued with the same activities.

Oats

This was usually the major crop planted and was found to be quite tolerant to a variety of growing conditions. In addition it was a very versatile crop being suitable for grazing, chaffing or thrashing for seed. Also it was much less draining on the soil than wheat. Until the coming of the tractor and a greater use of motor vehicles, replacing the horse, there was always a good demand for chaff, therefore a certain market providing a fair return.

Dad would recall that while in his latter time at school, Stubbs’, who were produce agents, offered Grandfather £8-0-0 a ton for all the chaff he could produce, which was almost double the then going rate. Grandfather put a big effort in and managed to provide 104 tons. Mr. Bill Mann from Bracknell worked as his stooker.

In producing chaff much labour was required. Cutting into sheaves would take place when the standing crop was still in the slightly sappy stage, then stooked and when sufficiently dried carted to a central stack. These stacks were usually located on a dry bank in a fenced off area and fairly close to one of the farm houses.

The stacks were built so as to shed water the aim being to prevent water getting into the stack and ruining the hay. Therefore in building the stack the sheaves would be placed so as to have a slight downward slant towards the outside wall as the stack grew, with the wall spreading outwards so as to provide an eave. The roof of the stack would also be thatched. The aim in each procedure being to prevent water entering the stack.

The thatching was mostly undertaken using straw, with wheat straw being favoured due to it having better water shedding qualities although it is said that earlier generations sometimes used reeds. Thatching would start at the eaves and move upwards layer by layer across the stack. The thatch would be kept in place by driving thatch pegs deep into the stack and then tying twine from peg to peg across each line on the stack roof.

Some skill and care was needed in stack building and thatching as if thatching was poorly done strong winds would sometimes lift the thatch allowing water to get into the hay. I remember Grandfather Badcock on more than one occasion relating the story that once his Grandfather John when riding into Glenore to visit family found several of his grandsons thatching and considered that they were “showing too much peg”. It is said that he dismounted from his horse and gave them a lesson on how the job should be done.

Written by Ivan Badcock.