The Launceston & Western Railway was officially declared open for business on Friday, February 10, 1871 now 135 years ago. On completion, it was described as the greatest work ever undertaken in Tasmania to that time. Its length was 45 miles and ran from Deloraine to the Port of Launceston, with the rail gauge at opening being the broad gauge of 5 feet 3 inches, this chosen to be compatible with the Victorian rail system.

Probably all of us here are familiar to some degree with the railway in Tasmania, for we see it as we travel along roads, it often running parallel with these roads or nearby, while at other times their tracks cross. Most of us here have probably travelled aboard passenger trains in the past, which until the 1950s were hauled by steam engines but after that time by diesel-electric locomotives. The Tasman Limited, although a slow means of travel, was for many years enjoyed by its patrons. The rail gauge was soon standardized to 3 feet 6 inches to be compatible to the Hobart to Launceston line which had been opened two years after that of the Launceston & Western rail line. For a time the original line between Deloraine and Launceston had a third rail, this to accommodate both the broad gauge and narrow gauge rolling stock. The last train using the broad gauge ran in 1888.

The railway in Tasmania has assisted much in the States development over its 135-year history, but at the same time has often been shrouded in much controversy and which still continues today.

One of the first proponents of the Launceston to Deloraine line was Mr. Adye Douglas, a prominent community leader in the Launceston area. In the early 1850s he first aired the concept of a railway for the region and from which interest gradually took hold. In 1855 this same Mr. Douglas, as a member of the Tasmanian Legislative Council moved in parliament that a survey of a proposed line between Launceston and Deloraine be undertaken.

The purpose of this was to improve the transport of a large amount of agricultural produce being grown in the area. A picture of this production may be had from the 1863 agricultural census in the Municipalities being traversed by the proposed line and which accounted for 50% of the States exports. Livestock was numerous there being 7,917 horses, 32,615 head of cattle, 240,777 sheep, 12,775 pigs and 531 goats. Cropping was also extensive with some 32,220 acres being sown to wheat, with other crops occupying a further 30,000 acres.

Almost all of this produce had to be moved to market which was to Launceston and beyond, including to the Mainland States and overseas. At the time Tasmania and particularly northern Tasmania was known as the granary of Australia.

The effort in moving this produce was considerable, the grain being moved by horses and wagons, which from Deloraine could take up to three days when the weather and roads were poor. Newspaper reports of the time tell us that these roads had many deep holes and were often wet and boggy for 9 months of the year. The carting of the grain crop would go on for up to three months from harvest. The livestock would be moved by droving, again a slow and arduous process.

Thus it had become clear that an improved mode of transport had become essential and at the time a railway was the only option.

James Sprent, the Government surveyor, soon completed a survey, with three routes to Deloraine being presented. One route travelled out of Launceston roughly following the Westbury road over the Sandhill but this was ruled out as being too steep, while the second and third routes followed the same line as far as Longford, initially travelling out of Launceston following the North Esk river, reaching Jiggler’s Valley (In 2020, Jigglers is known as Jinglers), then onto Evandale, Perth and Longford. From Longford, one survey took the line to Cressy and then swung back towards Deloraine. However, in the interests of cost, the final route chosen was the shorter route which travelled from Longford to Little Hampton, Bishopsbourne, the Oaks, Hagley, Westbury, Exton and finally reaching Deloraine, a distance of 45 miles. During construction, a minor change occurred at Bishopsbourne when suitable foundations for the bridge over the Liffey river could not be found, with the line being moved a half-mile northwards towards Carrick.

Opposition to the proposal soon surfaced from the southern representatives who dominated the Tasmanian parliament, their fear being that Launceston through the railway would gain an unfair advantage and became the chief port for the States trade. This opposition was also fuelled by pressure from southern commercial interests who had large investments in the Mersey region and who lobbied their southern Tasmanian parliamentary representatives to support an alternate Latrobe to Deloraine line, their hope being to scuttle the Launceston to Deloraine proposal.

After a delay of nine years, the Tasmanian parliament in 1865 finally relented and approved a Bill to allow the Launceston & Western Railway to proceed, but subject to several onerous conditions – the proponents to provide working capital of £100,000-0-0 and the landowners in the rail district agree to cover losses should these occur. With a total population including men, women and children being little more than 21,000 people in the area being covered, and the State being in recession, the raising of this amount of money was an impossibility. After further representation, the Government reluctantly agreed to reduce the capital requirement to £50,000-0-0 but not waive the required guarantee against losses.

It had not gone unnoticed by the Launceston and Western Railway proponents and residents of the north, that when Parliament had approved the Latrobe to Deloraine tramway the previous year, no guarantees had been imposed and further, a large land grant had been made to assist. Also at this time the Tasmanian Government was in the process of planning and building a Hobart to Launceston railway with the cost to be borne by a levy on all Tasmanians.

Various attempts were made to induce the Government to undertake the construction of the Western line as a public work, but for one reason or another, all these failed.

The injustice of this was keenly felt by the citizens covered by the proposed Launceston to Deloraine line and eventually would lead to many conflicts, including riots in Launceston and the rail line districts.

As part of the Government approval, a poll of those living in Launceston and the rail district was required. This was taken on December 18, 1865 and resulted in over an 80% margin in favour, for 2,238, against 544, an overwhelming majority of 1,694. The next day The Examiner newspaper reported, “The greatest excitement prevailed in Launceston and throughout the railway district generally on polling day, and when the result was made known, at 8 o’clock in the evening, from the balcony of the Launceston Hotel, by the Mayor, Alderman Douglas Esq., MHA, the tremendous cheering which burst forth from the throats of some 4,000 eager listeners marked the first great victory in the railway cause.”

To mark the occasion the Launceston Examiner, on the day of the poll, printed its newspaper in blue ink, the colours of the railway.

The first sod for the construction of the line was turned on January 15, 1868. In that year the Duke of Edinburgh was making the first Royal visit to Australia since its foundation and the members of the Launceston and Western Railway Company decided to link a “first” with a “first” and ask him to perform a commencing ceremony.

The Examiner newspaper went on to report, “Launceston was decked out as never before …… cavalcades of horsemen escorted the Royal visitor. Howitzers of the Volunteer Artillery Corps. gave a joyful cannonade and over 4,000 Sunday school children sung in welcome.”

Some of the items used by the Duke of Edinburgh at the opening ceremony have survived, the specially made wheelbarrow and the silver spade and are on display in the rail section at the Inveresk museum.

In July 1868 the tender of Messrs Overend & Robb for the construction of the line for the sum of £200,671-8s.-5d. was accepted. At the same time orders were sent to England for rolling stock, rails and the immense iron bridge required for spanning the South Esk River at Longford. The rolling stock consisted of four “powerful” locomotives of 36 tons each, 40 goods wagons and a number of carriages.

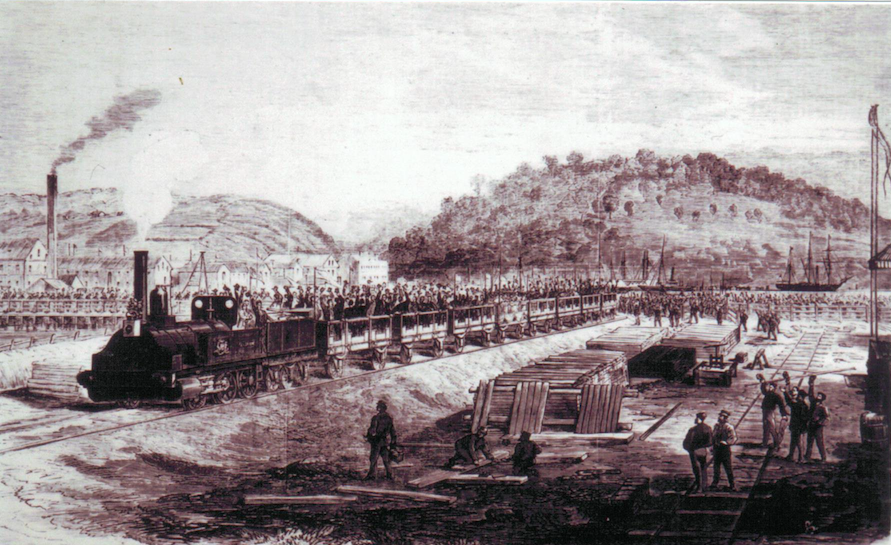

Work was commenced during the following August and progressed steadily until Thursday, August 19, 1869 when the section nearest Launceston having been completed, “the first ride on the rail” took place. This was to Jiggler’s Valley a distance of 6½ miles.

The first journey was the cause of much celebration, an official party was gathered together, consisting of the directors of the Corporations of Launceston and Hobart Town, and the leading residents of Launceston and the neighbourhood. The general public were allowed to use the train after the official trip had taken place, and upwards of 4,000 persons availed themselves to the liberality of the contractors. In the evening a grand banquet took place in the Mechanic’s Institute.

Also as a part of this celebration to mark the start of the rail, a 1,000 seat, two-storied timber grandstand was built at the station for spectators to witness the grand event.

When the great iron bridge was being put into place over the South Esk River at Longford, there was considerable interest and excitement amongst the locals, who in great numbers regularly visited the site to watch progress. This bridge had been built in England and brought to the South Esk River in sections. A particular interest was the building of a supporting centre pier in the middle of the river. This was achieved by shoring up the pier area by a timber casing and pumping out the water to allow excavations to proceed. The pump used was steam-driven with a capacity of 300 gallons of water per minute. The building of the bridge at the time was considered a major Colonial engineering feat.

There was further excitement at Longford when the owner of “Mountford”, Sandy Clerke, on becoming concerned about his farm being cut in two by the line, armed his workers with forks and staves and ordered them to take up defensive positions along the boundary fence, so as to prevent rail construction workers entering his property. Negotiations ensued with the contractors eventually agreeing to build a bridge to connect both sections of the property, bringing an end to the conflict.

The workforce employed on the line was considerable and when the Westbury to Deloraine section was being constructed, the Company utilized some 500 men, 70 horses, 50 bullocks, 25 drays, 115 three-wheeled “dobbin” carts, 47 wagons and 250 wheelbarrows.

During the construction of the line, a number of difficulties and delays were encountered, including washaways and mudslides due to heavy rain. A particular delay occurred due to the loss of rails being transported from England aboard the 2,116 ton sailing vessel the “Royal Standard”. The ship had become dismasted off the coast of South America and while under jury sail some 150 miles from Rio de Janeiro, ran onto a sandbank, broke in two and sank. Not only were the rails lost but also eight of the crew of 80.

To maintain contact along the 45 miles of line it was initially proposed to install an electric telegraph, however, the three commissioners who had oversight of the rail project declined the system due to cost, this being estimated at £2,000-0s.-0d. and instead approved a semaphore system of signals. Tenders for the construction of 12 semaphore signals were subsequently advertised with a closing date of May 10, 1870.

However, the semaphore system was destined not to proceed with the Commissioners changing their minds and giving their approval to the first proposed electric telegraph system. Tenders for the supply and erection of 900 telegraph poles appeared in The Examiner newspaper on Saturday, February 25, 1871, two weeks after the opening of the line and came into operation some six months later.

The first recorded carriage of freight on the line occurred a few months before its official opening, when Mr. Nicholls a Longford storekeeper, arranged the carting of 130 tons of guano to Longford with the train on its return trip carrying 100 tons of wheat and flour. This caused considerable excitement at Longford.

One of the first passenger trains ran in April 1870 taking people to the Western Agricultural Show at Westbury, again bringing great excitement among the population at the time.

Another special passenger train ride for the whole length of the line to Deloraine occurred on February 8, 1871, two days before its official opening. This trip carried a number of the clergy and family members who were attending a combined Wesleyan Methodist and Congregational Churches Missionary Society meeting which was in session in Launceston. The train, consisting of one engine and a first-class carriage, left Launceston at 7.15am and returned at 5.30pm stopping at all stations with 1½ hours in Deloraine.

Possibly it was this trip that my Walker family relatives witnessed at Westbury. Amongst descendants, the story is still related about the first train to pass near their farmhouse. The whole family had gone down to the line to witness the event and as the train approached along the track, one of the family members suggested: “We had better stand back a little so as not to frighten the horses.” It would seem that people of 1871 were also struggling with changes in technology.

At long last on Friday, February 10, 1871 the first rail line in Tasmania was officially declared open by the then Tasmanian Governor, Charles Du Cane. At the time it was described as “the greatest work ever undertaken in Tasmania.”

On opening day a great crowd of people gathered at the Launceston station and at 10.15am in the midst of great ceremony, bunting and much cheering, the official party set off for Deloraine. The train consisted of five carriages, two breaks and a locomotive. Fifteen minutes later a second train was despatched, this carrying those not able to get on the first train and picking up passengers at stations along the way.

On the day the Mercury newspaper correspondent reported, “The progress of the train was watched with interest by the small knots of spectators at different points. The reapers paused in their work to assure themselves of the reality of the scene, and even the cattle gazed for a moment and scampered away, horses pricking up their ears and making involuntary canters as if for fear that they would be superseded by the iron horse.”

However things did not go entirely to plan on opening day as, at the end of the day when one of the engines was being shunted back to its storage shed, it ran off the line due to the points being incorrectly set. A further accident occurred three days later when two trains collided head-on near Evandale.

The arrival of the railway brought immediate and long lasting changes to the region. In The Examiner newspaper the day after opening, R. Pescodd & Son advised readers – “The Launceston and Western Railway being now permanently opened for traffic, a Vegetable, Fruit, Poultry and Dairy Products Market will be held at the Public Market, Charles-street Launceston, on Saturdays from 6 to 10 am, commencing first Saturday in next month (March); thereby giving the settlers in the railway districts an opportunity of selling their produce at town prices ……… etc.”

An indication of the difference between town and country prices is to be found in The Examiner Editorial of Thursday, March 9, 1871. “It will take time before the public fully realize the benefits of the railway. Some years ago all that could be obtained for eggs at Deloraine was 2d. per dozen while in Launceston they were selling at 15d. per dozen and considered cheap at that price. Now eggs, butter, bacon, ham, poultry, pigs and many other articles that can be reared on the farm, might be sources of profit to the producer.”

Around two weeks later the Examiner’s Westbury correspondent noted a significant change for the town, writing as follows – “Future chroniclers of the history of Westbury will note this 20th. day of March, 1871, as the last day upon which the old familiar four-horse coach rattled through the village ……… It is doubtless a sign of progress that the rattle of the coach wheels should be superseded by the whistle of the iron horse ….” The correspondent went on to say “The railway will do much to induce a better style of farming. Farmers are already beginning to put it to themselves, whether it will not be more to their advantage to send their grain to the railway station and employ their horses and men in getting their early crops in in good time and in other useful works about their farms , than to adhere to the old system of occupying two or three months of the most important season in the year in carting their grain into town instead, and there can be no doubt but that so soon as the Railway Company afford sheds and sidings at the stations in the agricultural portion of the district the rail will be greatly used, and a new era in farming operations will commence.” He also envisaged that the Westbury Autumn Exhibition might become the exhibition of the Colony.

The Post Office immediately turned to the rail for delivery of its mail to the region. On Saturday, April 1, 1871 it was advertised that mail services by rail would be twice daily (not Sunday) and would leave Launceston at 8.00 am. and 4.30 pm. and arrive at Launceston at 9.40 am. and 6.10 pm.

Freight costs at the opening of the line were from Deloraine, 11s.8d. per ton of 2,240 lbs. and from Westbury 9s.4d. per ton of 2,240 lbs. Fruit to be carried at similar rates but empty bags would be conveyed free of charge.

Traffic returns for the first 20 days were:-

– Passengers 2,660 (including the three race days)

– Fares – £451-18s.-9d.

– Goods – £284-1s.-4d.

However income was not sufficient to cover costs and this combined with considerable damage to the tracks and embankments due to flood rains, resulted in the closure of the line, with the Company going into receivership. This occurred on June 29, 1872 with its 109 staff laid-off and this only after 16 months of operations. Ownership was taken over by the State Government with the necessary and extensive repairs undertaken and then reopened for business.

Losses continued to accumulate and in accordance with the original approval the Government set about billing the guarantors. On the refusal of many to pay the demands, the Government pressed ahead with enforcing the guarantees given, with some 1,200 warrants issued to the people of Launceston and those living in the railway area along the line.

When this further demand was refused, the bailiffs were sent out to seize goods to enable payment, and which included the stock and machinery of merchants and farmers, artisans’ tools and household furniture, including a baby’s cradle.

The people and those living along the line went into instant revolt against the Government and the rate and took an oath not to pay the rate. Further in protest 22 Northern Tasmanian Justices of the Peace resigned their commissions.

At a meeting held at the Launceston Town Hall on December 12, 1872 some 600 adamant people attended, and spent the entire meeting cursing the levy and criticizing the Government.

The Government, obviously assuming that the noise would die down, remained determined and sent a team of collectors from Hobart, led by a Mr. Propsting, to collect the unpaid railway levies – in cash or merchandise.

Meanwhile, some of those who swore not to pay the rate were beginning to bow under stern Government pressure and quickly became the targets for the anger of Launceston citizens.

On February 5, 1874 around 300 Launcestonians marched through the streets behind the steady beat of sticks on kerosene tins. With passions mounting, palings were pulled from fences, stones collected with roofs becoming popular targets, then windows.

An attack on the Court House Hotel proved too much for a squad of policemen who had been shadowing the mob. The marchers saw the police coming and charged them with palings held aloft. With the policemen retreating, the mob continued its run of destruction at the Coach and Horse Hotel and the homes of several rate-paying citizens.

A collector of the railway levy, Mr. Boothman had his home vandalised. Mr. Douglas who had paid the rate, was subjected to a 10-minute loud booing before his home was attacked, while Mr. J. Mathews, a pawnbroker who also paid, watched helplessly as his store was demolished.

With much anger and resentment continuing at the seizure of property, the people organised themselves into bands for its rescue. At one auction to sell seized goods held at Bell’s Mart, Charles Street, Launceston, when the people were assembled there and the sale was about to begin, six men dressed in black as undertakers, wearing black gloves and grim expressions, with black crepe on their tall hats, walked into the saleroom. On their shoulders they carried an empty coffin and on its lid lay an axe. Their leader let it be known that the first person to bid at the sale would be beheaded and carried away in the coffin. No sale took place that day.

So menacing was the riotous behaviour in Launceston that it was found necessary to withdraw the rural police from their ordinary patrols, and to swear in special constables for the protection of terrified townspeople.

With feelings remaining high and trouble continuing, the Mayor of Launceston entered the fray by also calling on responsible citizens to volunteer as special constables and protect the town against mob rule. No one responded.

The Launceston Fire brigade was approached but refused, saying it was a brigade of firefighters, not street fighters.

Meanwhile, effigies of prominent Government and local figures were being hung in the streets and burned, coffins were being carried through the streets, covered in tar and also burned.

To all of this the Government, at the urgent request of Mr. Propsting, sent a contingent of 35 armed police from Hobart, while at the same time threatening to send around a gunboat. Interestingly when the armed contingent arrived at the outskirts of Launceston, the local authorities would not allow them to enter the town carrying their weapons and thus they arrived disarmed, significantly diminishing their effectiveness.

Things were little better in country districts. There many of the defaulters succeeded in barring out the bailiffs, who hesitated to execute the distress warrants entrusted to them, when they found a powerful mastiff, with a bad temper and a good set of teeth, jealously guarding the premises against the approach of all strangers.

Another refusing to pay was Mr. Griffin of Deloraine. His horse was seized and taken to auction with the only bid received being from Mr. Griffin for one shilling. The bid was not accepted with Mr. Griffin stating his intention to take legal action against the Government for their non acceptance of his bid. The horse was then taken to Launceston where it was again offered for sale amid “a babble of yells, jeers and ironical cheers”. Mr. Griffin protested against the sale on the ground that he had already offered to buy the horse for one shilling, and harangued the crowd about the inequity of the railway rate.

The highest bid made was for 2d. When this bid was made two men made their way through the cheering crowd carrying a coffin, as a warning of what the purchaser of the horse would receive if he completed his purchase.

Finally amid riotous scenes it was announced that the horse had been sold to the Government for £5-15s.-0d.

Eventually, the story had a happy ending. The people collected a one penny subscription from residents to repurchase the horse. The Government got its railway rate, paid for in copper coins, and Mr. Griffin got his horseback.

The scene was set for major confrontation but with a change of Government, the railway levy was dropped by the new Government, with calm again returning to the region.

On the day of the opening of the Railway, the Editorial in the Launceston Examiner newspaper noted, “The railway is an accomplished fact, whether to realise the hopes of its friends or the predictions of its foes, remains to be seen.”

On looking back perhaps the proponents and the opponents were both partly right in their views, but yet at the end of 135 years the railway remains and although having seen many changes, still continues to fulfil much of the vision of its founders, transporting quickly and efficiently significant tonnages of produce between markets.

Notes for a talk to the Tasmanian Family History Society on April 18, 2006

by Ivan Badcock